Making the case for film on «Power Play»

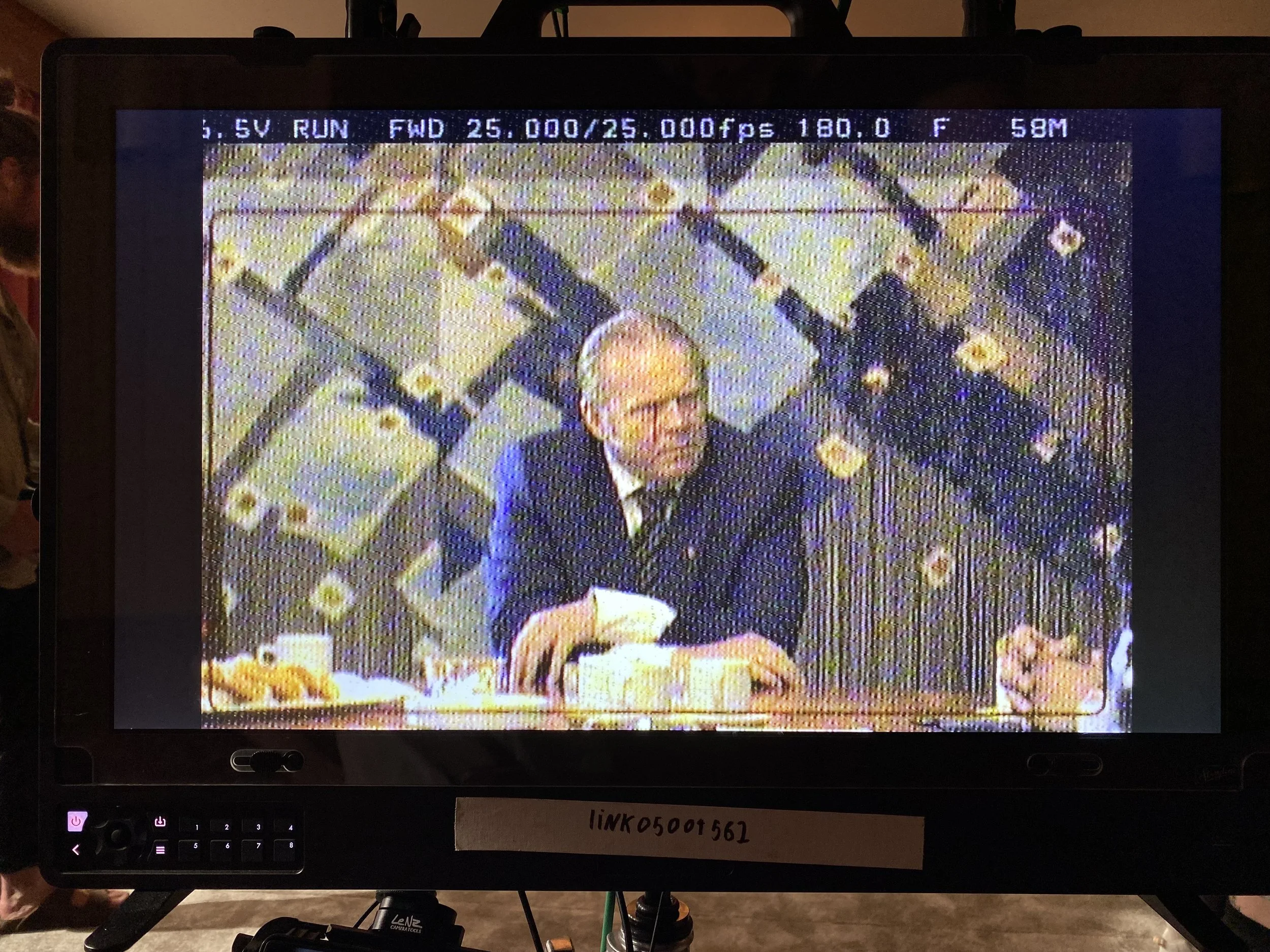

«Power Play» premiered in Norway this month, after winning Best Drama at Canneseries earlier this year and a special mention at Prix Europa. The show can be (roughly) described as the fictional origin story of Norway’s (arguably) most famous politician Gro Harlem Brundtland, who rose to power in the 70s amid an intense power struggle within the Norwegian labour party. I had the immense pleasure of setting up the cinematic language, lensing episodes 1, 2, 5 and 6.

The introductory pitch when I was approached was that the project should look as if a group of anarchists found a camera in a trash can, and decided to make 12 hours of TV drama about politics. I immediately brought up 24 Hour Party People, which it turned out everyone was poring over already. With such a grungy reference, I felt it was appropriate to seek a different texture than the expected digital palette. MiniDV was brought up, but was not deemed marketable by distributors. I’d done a lot of 16mm for shorter projects, and really love the texture, as well as the workflow, so I suggested we try to shoot it on film. It cost me about a month of prep to push this over the line, but our producers were very supportive and went out of their way to investigate how we could achieve it practically and financially. Film is still used on (some) movies in Norway, but even then it’s a battle to make it happen. Long story short, we managed to get the green light and started loading our magazines.

There are endless debates and comparisons arguing film vs. digital, and I hate to be an evangelist of one or the other. Steve Yedlin famously demonstrated how 35mm and Alexa could look indistinguishable, while the likes of Cristopher Nolan and Tarantino insist on analog capture. I agree that you in theory can make a digital picture look like almost anything, but I would like to argue the case for film on certain projects.

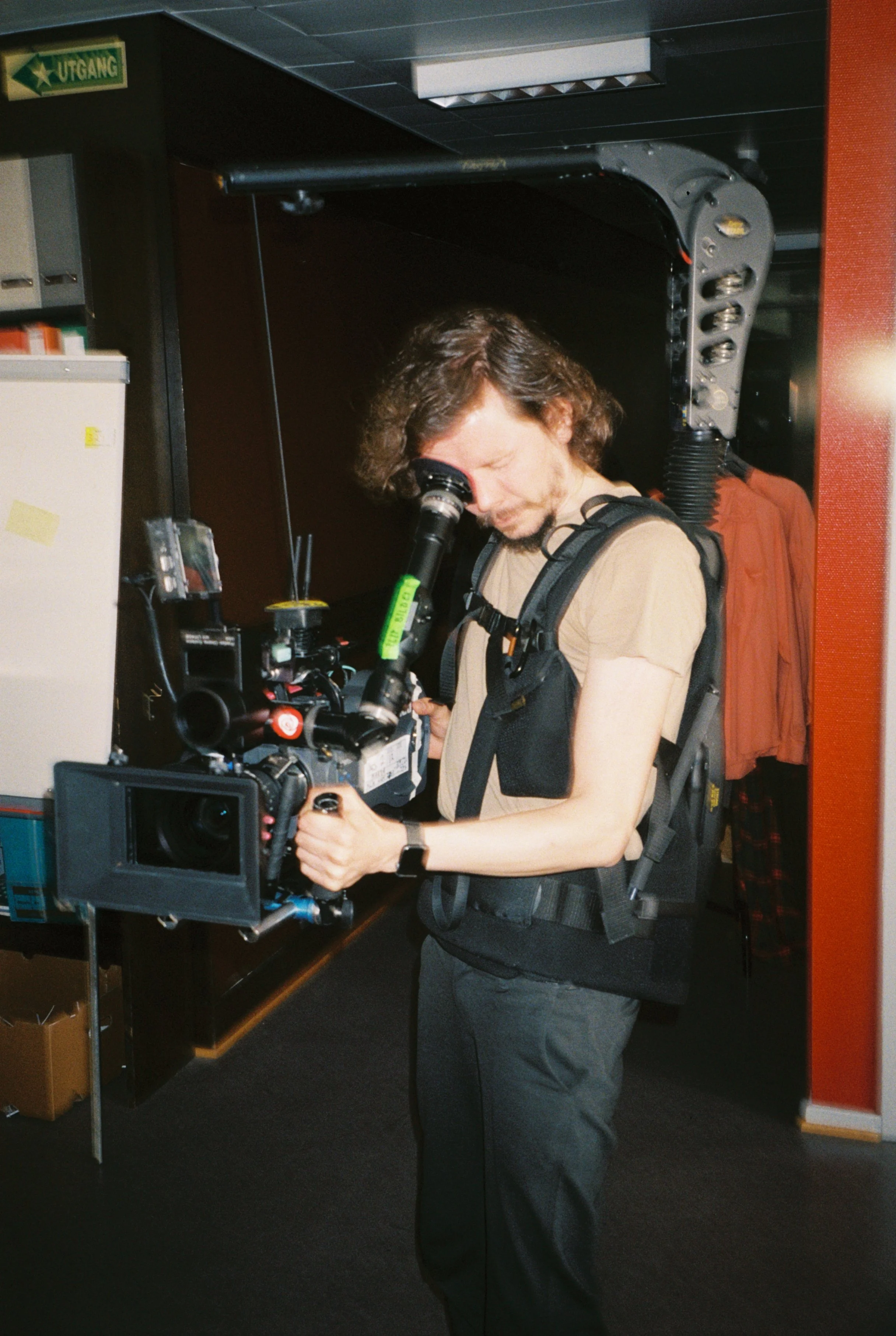

We wanted this project to look different, but we also wanted the whole mentality of the shoot to be different. Filmmaking is teamwork, and to make something extraordinary, you need to inspire all your teammembers to play the same tune. Our director Yngvild Sve Flikke was adamant that we should embrace the «camera from a trash can»-metaphor as literally as possible, and try to design a run and gun approach to period drama. I was very comfortable with the robustness of the 16mm negative, and felt it would be suitable in a wide range of lighting conditions. I thought we could try to minimize our camera and lighting crews, use simple methods for manipulating available light or just a few artificial light sources, and work without monitors. I’d mostly have the camera on my shoulder with a zoom, dancing with the actors in long takes where the camera just reads the situation and reacts to what the characters say and do.

An initial fear was that the crew would oppose not having the luxury of massive video villages that by now have become dominant on most shoots. The script supervisor maybe felt the most fragile, but was also then helped a lot by everyone else being on their toes. I sometimes find that video villages passify crews, but not having the tent forced people to engage and be proactive. The cast also embraced shooting on film, and in extension through the style of the cinematography, a more open ended approach to blocking and filming. Without all the limitations imposed by a big machinery, there was actual improvisation and discovery on set. Not to say we went off script all the time – there was always a strong backbone in the written material, but the creative process was very much alive on the shoot.

We quickly developed an appreciation for the sanctity of the take. I’ve had many actors tell me how they become insecure when the camera is rolling all the time. They never know when it’s for real, and end up potentially spreading out their energy too thin, or committing too much at the wrong moment. When our camera turned over, they knew it was for real, and combined with a fluid shooting style that would rather have few wandering shots than shoot coverage, the actors could play off each other. I think Yngvild’s dream was for all of us to play together like a band, tuning in to each other’s rhythms and sensibilities, and tagging along if someone decided to play a solo. And in the end I feel that was exactly what we achieved.

Workflow aside, film was first of all an aesthetic choice. While Steve Yedlin has proven that you can emulate the look of film by breaking down the components of what a film look is (grain, halation, gate weave) and emulating the colour rendition through maths, there are in my mind a few aspects we tend to forget about.

When I shoot digital, there is a high resolution monitor right there showing me more or less exactly what the camera sees, or what my LUT interprets it to be. There is a strong urge to tinker with the image using more and more complex lighting setups. And I realize that the more I tinker, the more I’m making it look like something I’ve seen somewhere else on a screen. Subconsciously I’m copying whatever has inspired me lately from one of the thousands of screens I’m surrounded by in daily life. And I have to work really hard with my own mental process to be aware of this and surpress that impulse.

When I shoot film, I don’t really know exactly how it will come out in the end. I have my craft and my experience to help me picture it in my head, but I’m not afforded the luxury of seeing exactly how the exposure pans out. So I light whatever intention I have using my eye and my light meter. I’m immediately more likely to recognize simple beauty and unique moods that arise, and less inclined to compare with projected impressions I’ve been subjected to lately, or start polishing insignificant details. It’s a different sensory experience, and really quite liberating. But it also creates a different image than I would have on a digital format. I’ve made a habit of sometimes making a change «blind» on digital shoots, and call ready without confirming it in a monitor, because I want to push myself to make the image inside my head and in the physical space, not on the screen.

Another aspect is that the look and feel of the medium is already locked into the picture when you get to the grade. Yes you can emulate it on top of a raw digital acquisition, but you can also choose to not emulate it. Or emulate something else. I strongly believe that endless choices are a natural enemy to human creativity. We enjoy creating within boundaries. Not to mention that a modern post production process involves a lot of people who are allowed a say on the final look. It helps our craft as cinematographers that some of our choices are literally burned into the negative. The same impulse to immitate something else that I get on a high resolution on-set monitor, is to an even larger degree present in the grade. Only strengthened by these other participants experiencing the same impulse without the same awareness of it.

I’ve chatted with colourists who support a suspicion I’ve had. It’s «easy» to shoot film and digital side by side and then emulate the film look on the digital frame to a point where not even professionals can tell the difference. It’s a completely different thing to receive a batch of digital material with no analog reference and do the same. You could apply the colour science and the effects you know would be there, but there is a certain degree of randomness involved in the chemical process – how the film reacts to the light hitting it and how it develops, that’s hard to predict. I’ve heard from colleagues who experiment with bringing a film camera to shoot a couple of frames in each scene, just to see how the film would react in a certain environment or light, and using it as a reference in grading later. Steve Yedlin debunks some of these mysteries, but I’ve done enough overexposing, underexposing, push/pull processing and cross processing to say with confidence that analog acquisition opens a realm of exciting unpredictability that digital does not have.

In the end, my pet peeve is the freedom of choice. We should respect that film does bring something that can’t be broken down into numbers, while also being honest about what can be achieved on a digital image in terms of emulating the look. On behalf of cinematography as an art form, I hope we can work consciously to preserve the ecosystem needed to keep film alive. Which means supporting Kodak and the labs, and making sure camera rentals maintain the equipment and keep educating technicians on the process. Kodak are already making decreasing amounts of raw stock, which was initially a worry when we called to make a purchase for 12 episodes: They were not immediately sure they could make that much. We’ve already lost the Norwegian film lab years ago, and the only Scandinavian lab is in Sweden. If we accept that we should emulate everything digitally in the future, analog capture surely will die.

«Power Play» was made with the technical support of Storyline Studios in Norway who advised our production on the pipeline needed to maintain a film workflow for 120 days, and supplied the camera and light equipment. Kim Bach was my go-to consultant there, while Mai Dehli kept lenses and cameras in tune. Kodak supplied 125000 meters of Vision3 500T 16mm film through their Finnish supplier Mutascan. Cinelab UK handled development and scanning. Film was shipped from Oslo to London on a daily basis, and came back as digital deliveries to our editors in Oslo. Dailies were graded by Darren Rae at Cinelab in London, who then transfered the CDL-data to Storyline where final grading took place with colorist Camilla Holst Vea, using the dailies grade as a non-destructive starting point. Kjetil Fodnes was my focus puller and technical lead in our camera department, while Torstein Sandven loaded magazines. Isabell Dahlén was gaffer with best boy Kristian Holten. The series is produced by Motlys and Novemberfilm.

(Apologies to Steve Yedlin for calling him out three times. I have the utmost respect for the work he’s done on digital image pipelines.)